Like politicians in some failing political party that is

slightly past its ‘sell by’ date, the Egyptian gods were represented by some

pretty odd and wacky characters. Some,

Frankenstein like, were made from bits and bobs of animals and humans like

Ammit who I mentioned last week. Go on,

you know you’ve voted for someone like that in the past.

Looking pretty strange was an obvious occupational challenge

for the rulers of the afterlife, and there were lots of mysterious denizens of

the Egyptian pantheon that I could choose to illustrate. There is Sobek, a crocodile headed god, and

Horus a deity in the shape of a falcon.

There was a hippopotamus headed goddess named Taweret, the goddess of

childbirth, and Bes, a distinctly weird looking gentleman – chunky in build,

entirely blue and with a lion’s mane.

When an Egyptian died, a number of different spirits were

supposedly released, among them the Ka, the Akh and the Ba. They all have different powers and

represent aspects of the deceased; the Akh for instance represented

their immortality, while the Ka was their life force or genius. The Ba represented their character,

the things that made them what they were, and is represented by a human headed

bird, with human arms. In Book Of The

Dead manuscripts these Ba birds along with the other spirits are seen

present at a funeral hovering near the deceased while they carry through

various duties, saying prayers and spells, worshipping, and waiting for their

moment to re-enter the corpse.

Ba’s were also able to re-visit our world in a

variety of forms. Recalling Anubis and

his weighing of the heart, the Ba was also the poor unfortunate that had

to witness this important procedure, no doubt biting its nails (remember, its got

hands) as to the result. They look cool

and elegant in the manuscripts, and I might have a try at illustrating one.

|

| Bast scribbles. Left Bast examines the world - right, Bast preying. |

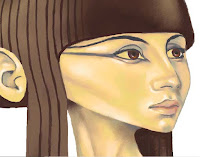

But using Bast as my first project, I wanted to do a larger

study of the head and settle on another pleasing (to me anyway) position for

the arms and hands. First I used the

previous approach, black with blue outline, which I was happy with, but then

using the same drawing (always on a separate layer from everything else) I gave

the image colour.

I felt that the colour range that I could use should be

reflected by actual animals (So green was mostly out – after all it’s a cat I’m

painting not a parrot) and blue outlines notwithstanding, a reddish yellow

colour set seemed the most appropriate.

|

| Bast scribbles. Figuring out posture and positioning of limbs. |

Using two or three colours allows for light and shade to be

applied, and therefore modelling of the surface. So the result is a more round and three-dimensional form, but it

can still be kept straightforward and simple.

The strong highlights are blended together, but have been deliberately

placed fairly roughly onto the figures for a sense of spontaneity. I colour the eye separately as I have done

with all the images up to now, as the eye is a focal point in the design,

always an important object in the depiction of any face.

|

| Finished designs with different body postures. |

That might seem an obvious thing to say, as if I were going

to then say that the nose or lips were not really that important and could be

left out of any portrait to save time.

I suppose its part of the design stage; the artist decides how a feature

is represented, from what angle it will be seen, and how well defined the

feature is. It is possible to paint a

face and have the eye be the first thing anyone sees. Design and composition can be complex.

|

| Bast designs comparing colours. |

Next I take the character of Anubis, and carry through a

similar process, a different position of head arms and hands, this time he his

holding some small jars instead of scales.

I think this new position shows him of as a jackal better than my first,

he has slightly bigger ears and a longer snout, his head being almost in profile. I’ve also given him and Bast more realistic

body shapes; here he has a neck, shoulders and a tapering waist, but, as with Bast, I’ve made

the design decision to leave the arms fairly ‘boneless’ so they can make fluid

curving shapes around the body.

|

| Anubis designs colour comparison. |

Here are some more design scribbles for an image of Sobek

the crocodile headed god I

|

| Sobek scribbles. I chose the one on the right to develop further. |

mentioned above.

Next week I will talk about this design and also experiment with CYMK

colour. As all these designs will to be

printed by the print on demand company Zazzle, then this colour type becomes

important, as it can affect the colours put down digitally using a RGB palette. And so, until next week.